How Coffee Cooperatives Help Ex-Rebels Rebuild Lives in the Southern Philippines – about the thesis of Moh. Shanizee Albani Sarabi

In the conflict-affected communities of Sulu in the southern Philippines, the scent of coffee now mingles with the memory of war. For decades, Sulu was a flashpoint of armed struggle, its people caught between poverty, historical injustice, and the pursuit of autonomy. Today, the same hills that once echoed with gunfire are filled with the sound of farmers harvesting coffee cherries. These are not ordinary farmers. Many of them are former rebels, men and women who once took up arms and have now taken up farming tools. Their journey from war to peace, from combat to cultivation, lies at the heart of my research. My study explored how membership in local coffee cooperatives can help former combatants rebuild their livelihoods and reintegrate into civilian life. It asks a simple but powerful question: Can a cup of coffee contribute to sustainable peace?

A New Path for Peace and Livelihoods

The Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, or BARMM, is among Southeast Asia’s most conflict-affected areas. Decades of armed struggle, marginalization, and institutional neglect have left deep scars on its people and economy. For many ex-combatants, laying down arms is only the beginning of a much harder battle: the fight to find purpose, dignity, and stability in civilian life. Without access to livelihoods, education, and social acceptance, former rebels risk being left behind or, worse, returning to the conditions that once pushed them into conflict.

Recognizing these challenges, the Philippine government and development organizations have begun supporting agricultural cooperatives as platforms for peace and reintegration. Coffee production, in particular, has emerged as a promising economic and social pathway. Sulu, despite its turbulent history, has become one of the country’s top coffee-producing provinces, contributing more than a quarter of the Philippines’ total output. This transformation is not accidental. Coffee thrives in the province’s fertile highlands, but more importantly, it thrives in its communities’ shared desire for change.

By joining cooperatives, former rebels gain access to credit, training, and market linkages that they could not achieve alone. Cooperatives serve as an anchor for economic participation and as a safe space where returnees can rebuild trust, reconnect with their neighbors, and redefine their identities not as combatants but as farmers and entrepreneurs.

Research Approach and Context

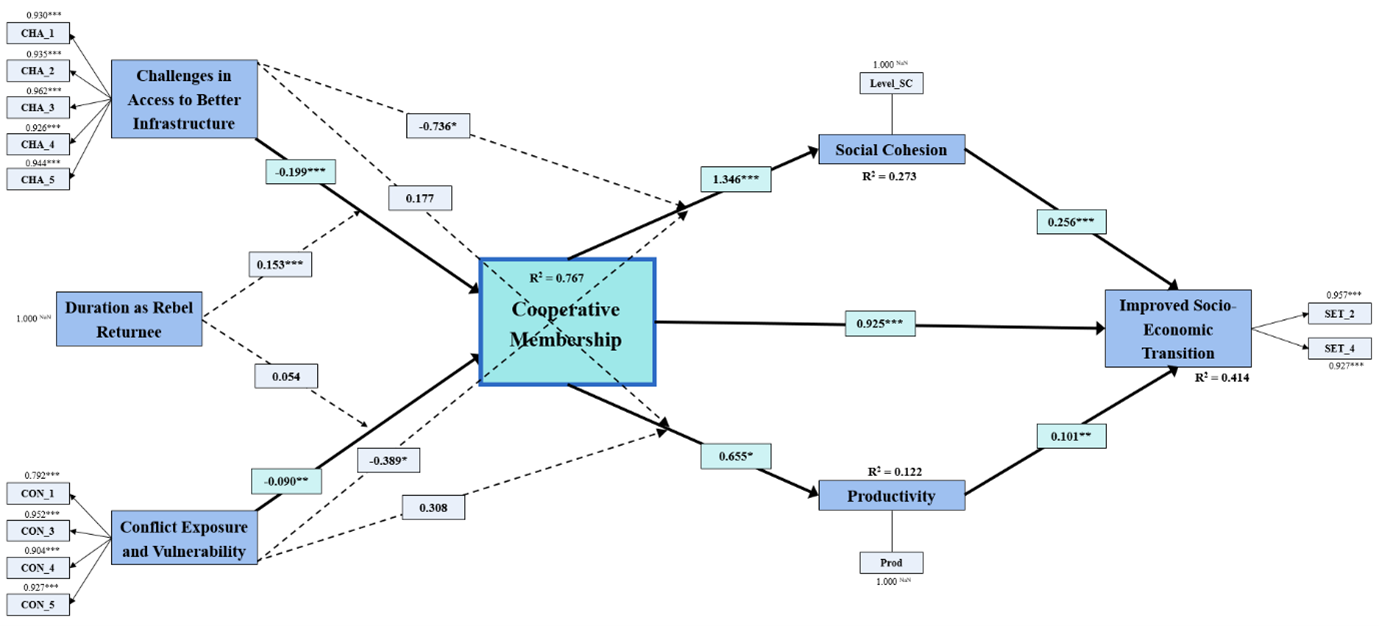

To understand the impact of these cooperatives, I collected survey data from 101 former rebels in Sulu, some of whom were members of the local Kantitap Consumers Cooperative. Using the Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) framework alongside social capital theory, I analyzed how cooperative membership is associated with economic outcomes such as productivity and income, as well as social outcomes such as trust and community participation.

The study employed a comparative cross-sectional design, combining descriptive statistics, regression models, and Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) to identify the underlying mechanisms of reintegration. While the quantitative results were central, the human stories behind the data were equally revealing. Many participants described how joining the cooperative not only improved their coffee yields but also helped them regain a sense of purpose and belonging after years of dislocation caused by armed conflict.

Insights and Transformative Outcomes

The findings of this study are clear and hopeful. Cooperative membership is strongly associated with better socio-economic outcomes. Members of coffee cooperatives reported higher levels of productivity, greater financial stability, and improved access to markets and government support. They were also more likely to adopt better farming practices and diversify their income sources. Participation in cooperatives allowed returnees to move from precarious livelihoods toward greater economic independence and security.

Education, farming experience, and the length of time since reintegration played a major role in determining whether a returnee joined a cooperative. Those who had spent more years back in civilian life and had developed stronger trust in community institutions were more willing to participate. Reintegration, therefore, is not a one-time event but a gradual process of rebuilding confidence, capacity, and connection.

Beyond economic progress, the research highlights that social capital is a vital foundation of sustainable reintegration. Within cooperatives, members formed close networks of trust, connected with other communities, and engaged with government and institutional partners. Together, these forms of social capital nurtured collaboration, accountability, and hope.

The results also underscore the importance of institutional support and governance quality. Cooperatives that received consistent guidance from local authorities, non-governmental organizations, and development partners were more resilient and inclusive. In contrast, where such support was absent, cooperative operations weakened and member participation declined. These insights affirm that reintegration succeeds not solely because of the individuals involved but because of the structures that sustain their transition.

Implications for Policy and Practice

The implications of this study reach far beyond Sulu or the Philippines. They contribute to a deeper understanding of how societies can sustain peace through inclusive and community-based economic systems. Cooperatives should not be viewed merely as instruments of livelihood generation. They are long-term reintegration mechanisms that restore both social relationships and economic opportunities.

For policymakers, this means designing reintegration programs that go beyond short-term cash assistance. Programs must emphasize inclusivity, cooperative governance, and the long-term strengthening of local institutions. For development organizations, investing in infrastructure such as roads, market centers, and storage facilities is critical, since poor connectivity limits the ability of farmers to participate in formal markets. Education and training must also be prioritized to equip returnees with leadership skills, financial literacy, and sustainable farming practices.

When international donors and peacebuilding agencies align their efforts with existing community structures like cooperatives, reintegration becomes more durable and context-sensitive. It also prevents the duplication of projects and ensures that resources flow directly to those who need them most. Ultimately, economic empowerment and social reconciliation are interdependent, and cooperatives demonstrate how these two goals can reinforce each other to achieve lasting peace.

Sowing Seeds to Brew Sustainable Peace

The story of Sulu’s coffee cooperatives offers a powerful lesson in resilience and transformation. It shows that peace can grow from the ground up when communities are empowered to cultivate their own future. For many of the ex-rebels who now work as coffee farmers, each bean harvested represents more than a product; it embodies dignity, stability, and belonging. Through collective labor and shared goals, these farmers have transformed landscapes of conflict into landscapes of livelihood.

As one cooperative member expressed during my fieldwork, “Before, we carried guns. Now we carry coffee cherries.” This simple statement reflects a profound shift from destruction to creation, from division to cooperation. It is a testament to the capacity of people to heal and rebuild when provided with trust, support, and opportunity.

Sulu’s experience reveals that sustainability is not only about environmental conservation but also about social cohesion and economic inclusion. A truly sustainable peace is one where communities are self-reliant, productive, and united by shared purpose. Coffee cooperatives, in this sense, are not only economic institutions but also symbols of transformation. They remind us that, with the right blend of trust, training, and tenacity, even the most fragile societies can sow the seeds of a sustainable and peaceful future.

About the Author

This article is based on the master’s thesis “The Role of Coffee Cooperatives in the Socio-Economic Transition of Rebel Returnees in Sulu, Southern Philippines” by Moh Shanizee Albani Sarabi, completed under the International Master of Science in Rural Development (IMRD) at Ghent University. Sarabi also went for exchange semesters to IMRD partner universities such as the Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra, Slovakia and the Can Tho University in Viet Nam. He graduated with an academic distinction of Summa Cum Laude.