Coping in Transition: Rural Sociocultural Resilience to Extractive Industries in Uganda

Resilience from a community, social, and cultural perspective

Resilience is characterized by multilevel processes used by various systems to achieve outcomes that are better than expected, especially in the face or wake of adversity.

Community resilience is appropriate for challenges with broader societal implications, such as shared resources (like shared water sources and agricultural land). Community stresses the importance of social interactions and relationships among stakeholders within a specific geographic area.

Lillian Anena borrows from Luloff & Krannich to define community as a network of relationships within a localized population, that meets the population’s daily needs through adaptive responses to changing conditions.

Why Community Sociocultural Resilience?

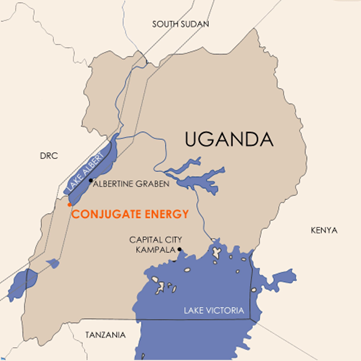

Image by conjugate energy

Tight-knit social structures build trust and provide grounds for conflict resolution, supporting individuals through shared goals and expectations of mutual support. Similarly, culture ensures the cohesiveness of a group, enabling disaster-affected groups to collaboratively enhance, retain, and maintain their identity.

Therefore, social resilience emphasizes the role of social structures, networks, and shared identities in fostering adaptability and sustainability. Conversely, cultural resilience emphasizes values, practices, beliefs, customs, and traditions in ensuring community continuity and identity amidst external challenges.

Lev Vygotsky's Sociocultural Theory supports the concept of sociocultural resilience. It posits that humans do not act directly with the world but their actions, cognitively and materially, are

mediated by material and symbolic artifacts including languages, numeracy, literacy, concepts, and forms of logic and rationality.

With that, Lillian Anena defined community sociocultural resilience as a community’s integrated and synergistic capacity to leverage its material and symbolic artifacts to navigate, adapt to, or recover from shocks and stressors.

To begin the investigation, she collected primary data over a period of five days using non-probability sampling techniques. She used purposive sampling to select focus group participants based on their experiences in the communities. For key informant interviews, she used snowballing where one participant from the study area recommended another.

She conducted three focus groups of six to seven participants and interviewed ten key informants. Participants represented community levels aligned with administrative units: sub-county, parish, and village. They were selected from diverse demographics, including government officials, community leaders, and residents.

She then utilized Thematic Analysis and identified patterns in the data that addressed the research gap. She also spent time observing communities go about their daily routines. In quoting participants, Lillian Anena used pseudonyms for key informants, and participant numbers for focus group participants to keep them anonymous.

How has oil and gas development affected rural communities?

The impact: “Our infrastructure has also developed…”

For impact, Lillian Anena utilized predetermined main themes adapted from the SDGs sustainability dimensions. She created the political dimension to capture power and agency dynamics within the communities and extractive industry actors. In all impact dimensions, community experiences were both positive and negative.

…we had no issues of theft here but these days there is always a report on theft…we do not feel safe because we always must keep watching around us. Is this how we shall continue to live?

Participant 1, Focus Group

Our infrastructure has also developed for example the health centre at Avogera which was a health centre III but is now a health centre IV.

Steven, Key Informant

Social impacts

These included increased food insecurity, forced migration, broken families from domestic violence, and safety and security concerns from migrants and authorities. However, some positive impacts included education and new skills, improved infrastructure like roads, equipped health centres, and hotels.

Political impacts

These included employment discrimination with professional jobs reserved for migrants, unsatisfactory governance from lack of transparency, insufficient compensation, and higher incidences of defiance and resistance from perceived unfair treatment.

Economic impacts

The most prevalent economic impacts were increased access to money through small businesses and casual jobs. However, there was higher cost of living from competition for resources with new settlers, and loss of assets and income sources like land.

Environmental impact

These included air and noise pollution, invasion from wild animals like elephants that further destroy crops, and loss of indigenous medicinal trees.

One of the new tarmacked main roads in Buliisa. In the background is a telephone masts that supports network coverage. By Lillian Anena

Influence on community sociocultural dynamics: “We lost our culture…”

To investigate resilience strategies adopted by affected communities, Lillian Anena first analysed how the impacts influenced their sociocultural dynamics. Sentiments towards sociocultural influence were mostly negative as was expressed by one key informant.

We lost our culture. They (people exploring new culture from migrants) think you are very primitive if you are still holding onto the culture. That you are not modernized and they like that word so much…Does modernization take away culture?

John, Key Informant

Shift towards urbanized lifestyle

Communities’ preferences shifted towards urban amenities like modern buildings over grass-thatched houses, water dams, and tarmacked road networks. Youths also preferred urban fashion discovered city migrants. However, changes in youth dress code were seen as inappropriate, with a preference for modest clothing.

Transformation in identity

Findings indicated women and girls’ empowerment in work like small businesses, education & training, and household responsibility. Belief in witchcraft as cause of diseases (especially HIV/AIDS) also reduced. However, some locals abandoned their indigenous languages for migrants’ languages.

Agricultural transformation

Agriculture experienced considerable changes, like new farming techniques, cultivation of improved crop varieties, and rearing improved livestock breeds. Farmers expressed dissatisfaction with the quality of newer varieties despite their yield capacity.

Transformation in traditional leadership

Due to bureaucratic processes of engaging with the extractive industry actors, local community leaders lost their ability to influence. Culturally, the Bagungu people of Buliisa installed their own traditional leaders after citing inadequate support from their mother kingdom of Bunyoro. This was because of the overwhelming negative impacts they were facing.

Small business owners display shoes for sale by the main road. In the background are public transport vehicles ferrying people in and out of the town. Lillian Anena

A woman prepares street food to sell to customers by the roadside late in the evening. Lillian Anena

A woman prepares street food to sell to customers by the roadside late in the evening. Lillian Anena

Resilience Strategies: “They are adopting new methods of farming…”

From the thematic analysis, Lillian Anena identified unique characteristics of the communities that translated into resilience strategies.

She found that some strategies, like value for education, were shared across the different community levels. As one focus group participant was quoted “Girl child education has also increased…the girls are now in school.”

Adopting sustainable livelihoods

There was a switch from traditional farming to adoption of improved farming practices. A key informant narrated that “They are adopting new methods of farming...there are new varieties of animals and crops that are coming up that used not to be there before.” This was done to improve food security.

Communities also showed higher interest towards skills improvement through education and training to boost employability.

Promoting harmonious coexistence

Communities maintain cohesion through mediation to resolve conflicts, creating new rules to promote safety, accepting changing roles of women, and welcoming migrants settling amongst them.

They also embraced women’s involvement in income generation and decision-making to reduce domestic violence. Similarly, contrary to the past, parents now enrol more girls in school.

Participating in collective action

Communities engage in collective action to fight against unfairness and acquire what they believe they deserve. A key informant narrated a recent occurrence where “Community members once threatened to light up and set the rig on fire…The noise and vibrations have become unbearable.”

Together, community members express their grievances, suggest solutions, and push for their needs to be met by relevant authorities.

Bridging knowledge gaps

Through capacity building and social learning, communities gain knowledge on road safety to avoid accidents, HIV/AIDS prevention to reduce the spread of this illness, and human rights to curb gender-related challenges. As Steven, a key informant states, “People have been greatly sensitized about HIV/AIDS and their capacity built especially on financial literacy.”

The communities have embraced formal education to acquire skills for formal jobs. They also stay informed about new occurrences through regular community meetings.

New cassava variety being sundried to increase its shelf-life. Lillian Anena

New cassava variety being sundried to increase its shelf-life. Lillian Anena

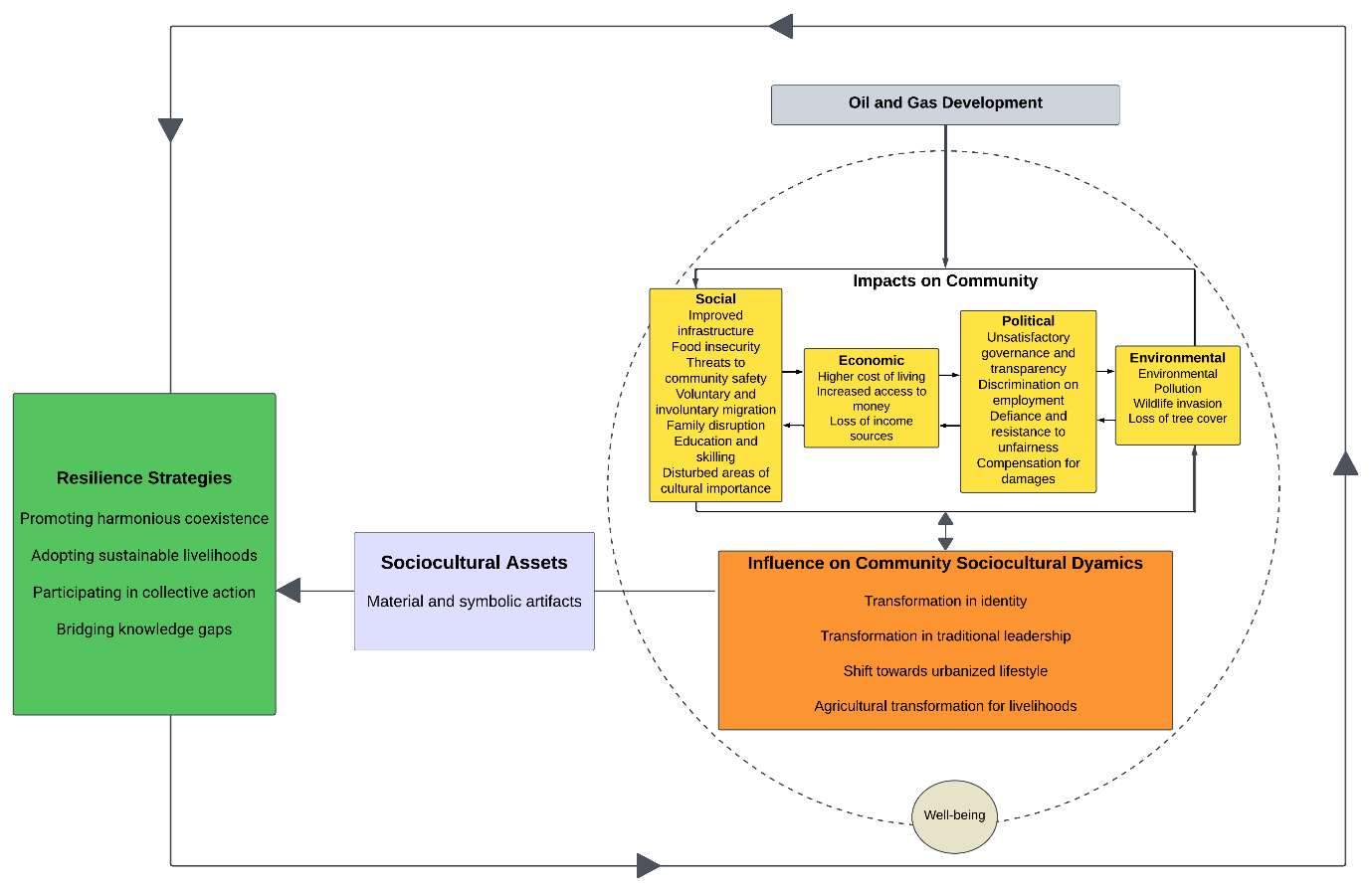

Conceptual framework for rural communities’ sociocultural resilience

To conceptualize the concepts, theories, and findings from the study, Lillian Anena developed a framework (See Figure 1). This framework can be adapted to further connect ideas around sociocultural resilience and rural communities in different risk contexts.

Extractive industries bring shocks and stressors experienced as multidimensional impacts in affected communities. The impacts cause sociocultural shifts which further increase or decrease the degree of impact. In experiencing impact and changing sociocultural dynamics, community well-being is also directly or indirectly affected.

Within changing sociocultural dynamics, communities harness their material and symbolic social and cultural assets to build resilience. With resilience being an ongoing process, affected communities continue utilizing and adapting the strategies to maintain stability.

A conceptual framework for community sociocultural resilience. Lillian Anena

What’s next?

The delicate balance between exploiting natural resources and ensuring that the well-being of the host communities is maintained, remains complex. While oil and gas development in the Albertine Graben increases Uganda’s hope for economic prosperity, it comes at a cost for the rural host communities.

Uganda’s goals for economic prosperity based on oil and gas development and the rural communities' lived experiences, are not in isolation from the SDGs specifically Goal 1: No poverty; Goal 3: Good Health and Well-being; Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth; and Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities.

Thus, Lillian Anena recommends relevant stakeholders to support community resilience by empowering local leaders, strengthening community security using neighbourhood watch, and revitalizing educational institutions to boost skill development. Such will increase safety, boost business and employability of skilled and educated locals to create lasting resilience.